Issue #6 focuses on representative learning design:

Representative Learning Design and Functionality of Research and Practice in Sport by Ross Pinder, Keith Davids, Ian Renshaw and Duarte Araujo (2011).

The internet recently has hyper-focused on soccer balls, walls and “ego armour”.

I am the last person to engage in defensive dialogue online, but that doesn’t mean I didn’t have so many things to say.

I think we missed the point. Our ability to critique task design in sport is not to attack those designing those tasks but rather to consider the effect those designs may have on the learners interacting with them.

I wanted to take this opportunity to talk you through what task design looks like for me. This means talking about a topic with a mouthful of a name, but an important one to learn nonetheless: representative learning design.

When I sat down to write this newsletter, I was tempted to avoid the phrase completely. I didn’t want to confuse any readers with the tough terminology. It’s not easy to dance around a term like this one, so I wanted to demonstrate my skilfulness as a writer and academic to follow the music.

But, in doing so, I am not giving you the opportunity to take up with the concept in its entirety. The issue is not the terminology but our use of it. Academic writing is not known for its storytelling or for bringing the reader along for the ride, so I started a newsletter instead.

This is me, doing my best to help you, the community coaches around the world, interact with a topic that we probably all use in some way. The language is not easy, but that does not mean we should avoid it at all cost.

Representative learning design (RLD)

What do we mean by ‘representative’?

The goal of RLD is to ‘represent’ the performance environment. If we want to train our learners to perform effectively when it matters, on game day, then we need to find a way to ‘represent’ the demands of game day at training.

This does not occur in isolation though, we cannot just wake up one morning and decide to use representative learning design. We may have our own versions of this, like game simulation training, but fundamentally, our baseline assumptions can differ.

Personally, I subscribe to the notion that our actions (movements) emerge directly from the way we interact with information in our environment. In other words, our movements are coupled to the information we perceive and vice versa.

This view is articulated in a classical quote from Gibson (1979, p. 223):

“we must perceive in order to move,

but we must also move in order to perceive.”

My favourite example of this is walking into a room for the first time: you don’t know what is in the room, so you cautiously peek around the door frame to see what is there. That action provides us with information that we didn’t have before, and now we can re-organise ourselves to walk through the door. If the door was blocked by a table or a chair, then we can either move that or walk around it. Walking into the room also provides other/new sources of information and which we can use to continue moving.

Now we can contextualise this in a sport setting.

In many sports, we often encourage learners to move into space. To find space, learners need to perceive where a ‘space’ may be, and then navigate themselves there. From this new position on the field/court, they may have a new perspective with new/different sources of information.

As information and movement are inextricably linked (also referred to as perception-action coupling), I need to consider this reciprocal relationship when I design my training sessions and coach in the moment.

This brings us back to the first question from this section: what is representativeness? Or in simpler terms, what needs to be real?

Thankfully, a seminal paper by Ross Pinder and colleagues (2011) has already done the heavy lifting in a sporting context - this is where the term “representative learning design” comes from. This concept was built upon the foundation of “representative design”, which was coined by Egon Brunswik (1956) for psychology and experimental design.

Now, we’ve already spoken about one key coupling (information-movement), but there is one more we need to cover here: the person-environment relationship. They are actually very closely related - as the environment provides information and our actions can influence this information: we need to capture this relationship as a whole to truly understand what is happening.

Our previous attempts at research, especially in psychology, have been biased towards just studying the person. We rarely consider the role of the environment, which has probably contributed to the overemphasis of the ‘coach’ in sport settings. If we believe that information and movement are inextricably linked, then we also believe that individual behaviour emerges from our interactions with the environment, and our environments shape our behaviours.

You will notice here that my practical examples above still apply.

So how do we achieve ‘representative design’? Pinder and colleagues (2011) summarise Brunswik’s (1956) view well:

Brunswik (1956) advocated that for the study of organism–environment interactions… “cues” (or perceptual variables) should be sampled from the organism’s typical environment so as to be representative of the environmental stimuli from which they have been adapted, and to which behaviour is intended to be generalised.

(emphasis added by me)

What does this actually mean?

As coaches, if we want to prepare our learners for the performance environment, then we need to represent it authentically. A learning environment, aka training session, should aim to sample the performance environment in a way that maintains the ‘stimuli’ (information sources).

The efficiency with which learners can use these information sources is part of the learning process. With exposure, discovery and experience, the information-movement couplings we are capable of improve with training.

But how do we know what to simulate, and how?

Well, lets start with the two components we already have: information and movement. In Pinder’s (2011) paper, they are discussed using different words: action fidelity and functionality.

Action fidelity refers to how effectively the actions athletes perform during training simulate the demands of their performance environment. In other words, are they behaving in the same way that they usually would, or be expected to, on game day?

Functionality is about ensuring the actions are based on realistic learning contexts or scenarios that would genuinely happen during the game.

So what needs to be real?

I’ve been asking myself that a lot lately. I have also had the pleasure of delivering a series of workshops for a variety of coaches in unique sporting contexts, so I’ve had some time to play around with different ways to talk about it.

I like to think of representative learning design as four domains:

Intentions

Actions

Information

Interactions

Intentions

“Hit the ball over the net” versus “Hit the ball past your opponent.”

At first glance, they seem like very similar instructions, but they reflect two very different intentions.

If we ask our learners to simply “hit the ball over the net”, they will organise their actions in a way that simply achieves this, and just enough to achieve this. If we want to maintain functionality, we need to simulate a realistic context, a problem to solve.

If we get to game day and our learner hits the ball over the net, but sets it up perfectly for their opponent to win the point… is this really a useful outcome?

We have to remember that many of our actions in sport are often inter-actions - connected to the intentions, the decisions we make, the environments we inhabit, the problems we are trying to solve. So much of sports performance is taking our action capabilities, the actions we are capable of making in response to the information we are perceiving, and responding in a way that gives us the competitive advantage.

It is very easy to train without knowing whether we have achieved that competitive advantage, and it starts with our intentions. An intention like “hit the ball past your opponent” determines that there must be an opponent present in the activity, and not just for show. They are actively competing against you, and how you respond to that (very realistic!) problem will likely bring very different actions compared to just “hitting the ball over the net”.

This intention is achieved in both versions, but one promotes more action fidelity and functionality than the other.

We can adjust our intentions over time and intentionally dial them up and down to suit the needs of our learner. I want to really emphasise this here: we have a responsibility to meet the needs of our learners as they are, right now, in front of us. As a coach, you may arrive at a session with a pre-prepared intention and subsequent session plan, but we need to be response-able to our learners.

If intentions are too complex or advanced, we risk overwhelming them. If intentions are too simple or deconstruct a skill instead of simplifying it, we risk developing skills that might work at training but not during the game.

Part of our role as coaches is to dial up and down the components of our learning environment effectively, especially if you believe that the environment itself plays a major reciprocal role in the emergence of behaviour, as I do.

Ultimately, this is why we apply representative learning design as coaches: we are preparing learners for the demands of game day by effectively sampling and presenting realistic problems that they can explore, discover and exploit at training.

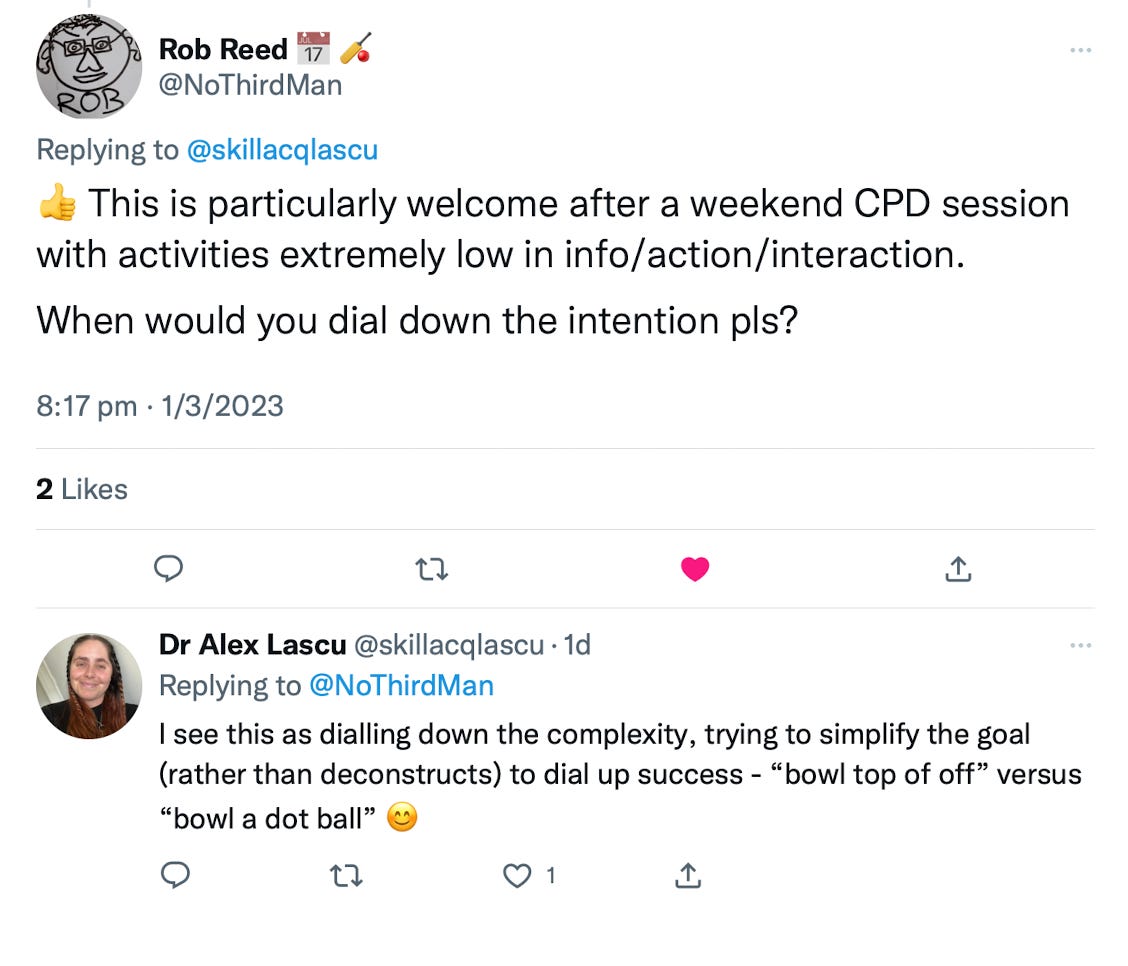

I was recently asked what it looks like ‘dial down’ intentions, and you can find my response below. When/why would you dial down your intentions during a training session? Feel free to add your response to this tweet 😁

We will talk about Actions, Information and Interactions next time!